The Reserve Bank’s interest rate tactic is based on flawed logic and will lead to unintended, but predictable consequences, suggests OpenCorp CEO MATT LEWISON.

Interest rates are seldom out of the news at the moment and with good reason. The Reserve Bank’s 10th successive interest rate hike in early March increased the financial pain for many households.

I’m often asked when interest rates will peak – and what happens at that point.

We all know why the Reserve Bank puts up interest rates – to drive down inflation, which we all agree is not ideal if allowed to spin out of control. But some of the logic behind raising interest rates at this time is a little flawed.

Flawed, you ask? Surely the RBA can’t be wrong? Well, I have always believed that the Reserve Bank economists are the smartest in the country. But their recent decisions and announcements suggest that they are not considering some unintended consequences that will be counter-productive to their objectives. To understand why we need a bit of Economics 101. The RBA has a mandate (set out in the Reserve Bank Act 1959) to:

- ensure the stability of the Australian currency,

- maintain full employment in Australia,

- and ensure the economic prosperity and welfare of Australians.

To do this, the RBA needs to control monetary policy.

It’s also important to note that nothing in the RBA mandate talks specifically about the housing market. The RBA aims to avoid the Australian currency depreciating, which happens when there is rampant inflation. Deflation isn’t exactly desirable either, as nobody wants to invest if the price of goods is dropping.

So, the goal is to deliver moderate and consistent inflation of between 2% and 3% per annum. This encourages investment, as people are more likely to invest when asset prices and wages are increasing consistently, which leads to economic growth and prosperity. Excessive inflation, on the other hand, can become self-fulfilling, which leads to all sorts of long-term issues.

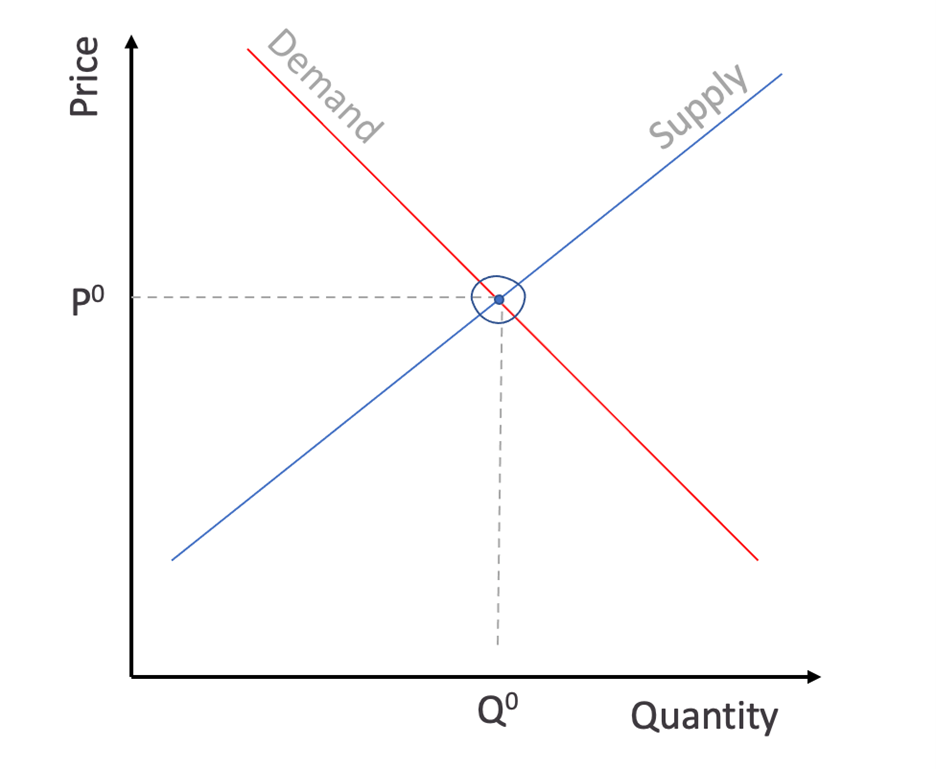

We monitor inflation against the consumer price index (CPI), which is a basket of goods that represents household expenditure. How does monetary policy impact inflation? Think of the classic supply and demand curve; where demand and supply meet is generally where the price settles.

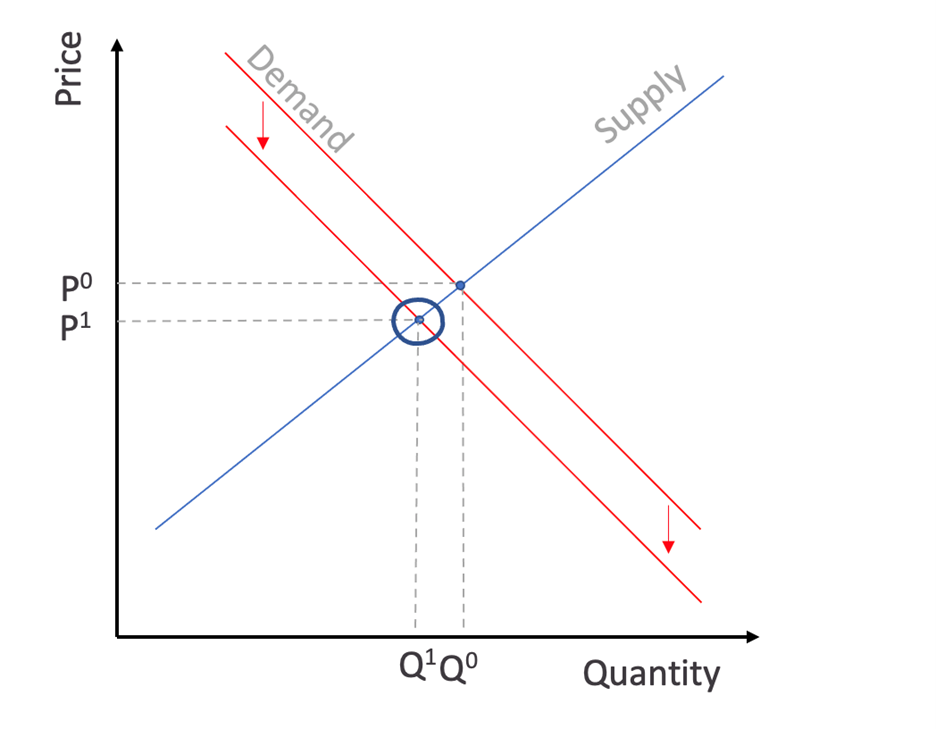

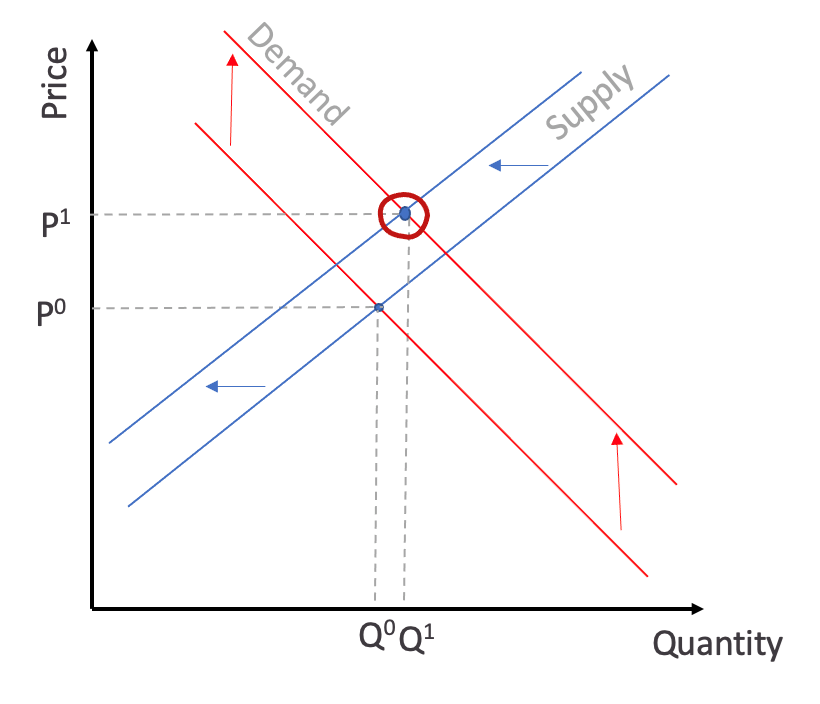

And if, through monetary policy, the RBA can lower the demand for goods without lowering the supply of goods, then (in theory) the price of those goods should drop. This is shown in the following chart where lower demand leads to fewer sales and a lower price:

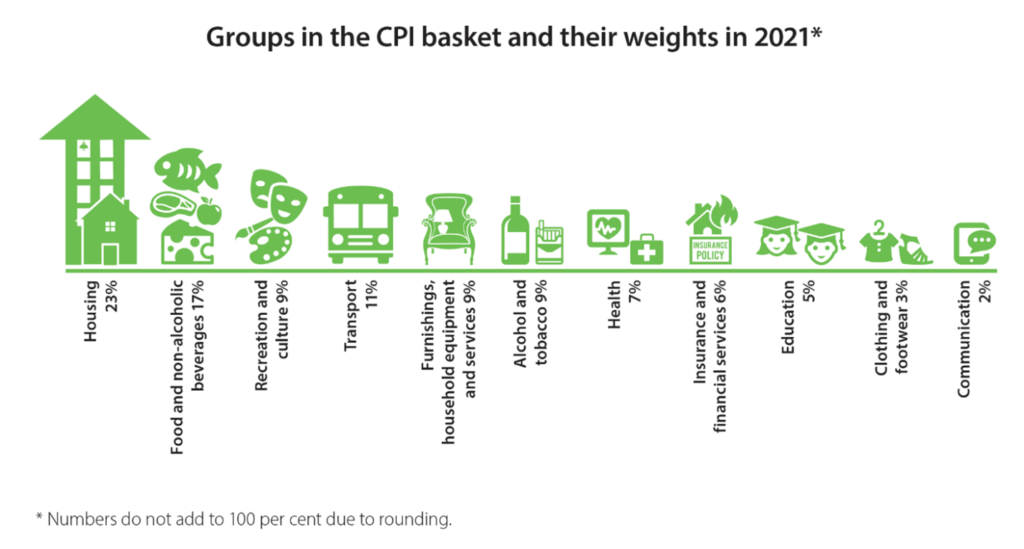

The RBA seeks to lower demand for goods and services by adjusting the interest rate, which increases the cost of borrowing, and most people’s biggest debt is their mortgage. If mortgage repayments go up, you’ve got less money for discretionary spending – and hence less demand for certain goods. (If you have no debt, of course, this mechanism does nothing.) The other mechanism the Reserve Bank has for influencing demand is to diminish consumer sentiment. If you’re scared about the future, you’re less likely to invest, as you want to put money away for a rainy day. More money saved = less money spent on goods and services. The next bit is where the theory enters a bit of a grey area. Back to the CPI; that basket of goods contains 87 different categories of items, with housing making up the biggest segment at 23%.

The CPI basket’s housing costs include 6.2% for rent and 8.2% for the purchase of new dwellings by owner-occupiers. This is a bit misleading and is one major reason why the RBA is struggling to work out what’s going on with inflation.

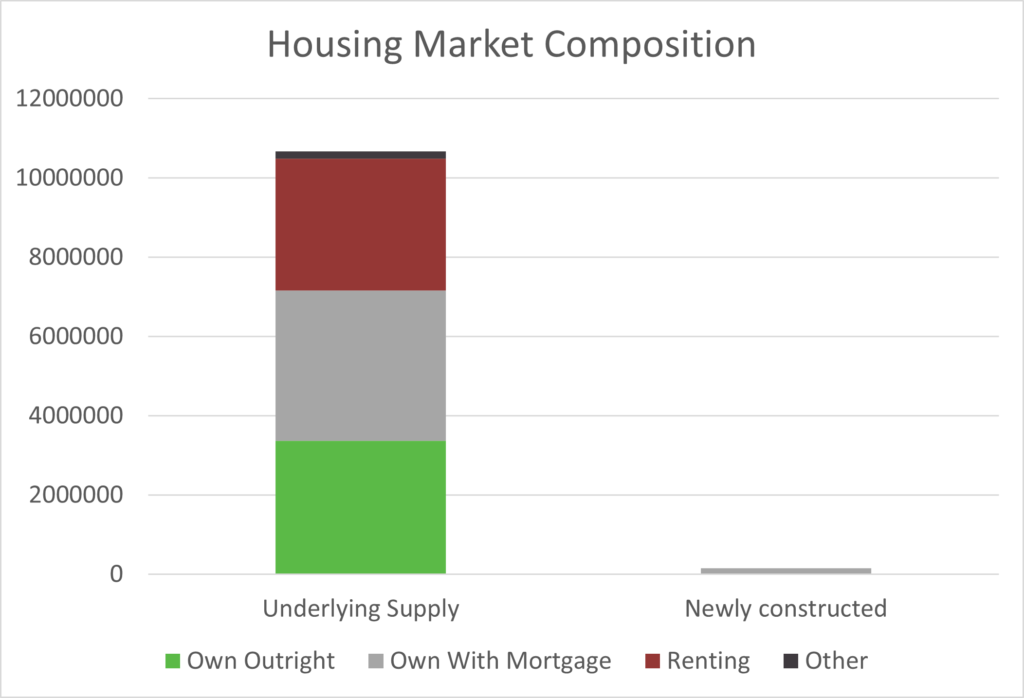

Firstly, let’s look at the purchase of new dwellings by owner-occupiers. This relates exclusively to the cost of building a new home. As we have all heard, housing costs increased substantially over the last couple of years. When the cost of building increases, it makes it harder for first-home buyers to enter the market by constructing new homes. The RBA is therefore right to be concerned, as higher construction costs will therefore reduce the supply of new dwellings. But, this is where the logic starts to fall apart. In Australia’s 2021 Census, there were 10,852,208 households counted. Each year, there are around 150,000 new owner-occupied dwellings constructed. So, in any given year, around 1.4% of households construct a new dwelling. It therefore seems disproportionate to allocate 8.2% of the CPI basket to a cost that is incurred by only 1.5% of households in any given year.

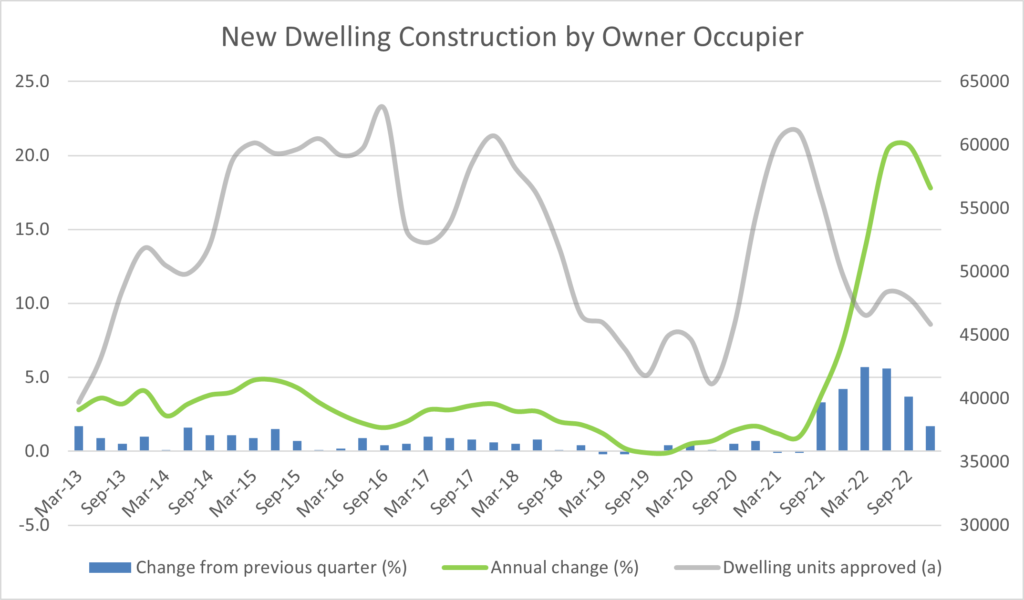

Further to this, the cost of building a house is only partially incurred by the 1.5% of households that build a new dwelling. The majority of the cost is covered by the bank, so the important factor is not the cost of the house, but the cost of paying the mortgage, that matters the most. When the RBA puts interest rates up to ensure that the cost of building a new home does not deter future buyers from building a new home, they are inadvertently increasing the cost of financing a new home which directly reduces the supply of new homes in the future. Finally, with regard to construction costs, the escalation that resulted from a combination of the government’s Homebuilder grant, which was announced in August 2020, and supply chain and logistics constraints, actually started to diminish before the RBA started increasing interest rates in 2022. The following chart shows clearly that the annual change in dwelling construction costs increased as a result of higher building approvals between mid-2020 and mid-2021, with a 12-month lag. It also shows that a year after housing approvals started to diminish, commencing mid-2021, construction cost increases also started to diminish.

The other major housing contributor to the CPI basket is residential rent. Again, the RBA is right to be concerned about rising rents, because higher rents hurt those with the least assets the most, but the logic behind increasing interest rates to stop rents from escalating is flawed and so is the allocation of 6.2% of the CPI basket.

Around half of Australia’s workforce are renters who spend around 30% of their household budget on rent. In fact, the median rent in Sydney is more than 40% of the median household wage – far more than the 6.2% allocated in the CPI basket. It’s by far the biggest cost that a household incurs, and due to the undersupply of housing across Australia, rents are rising steeply in many areas.

Vacancy rates are as low as they have been in the past 25 years and when there are low vacancy rates, there’s a lot of competition for rentals. When there is a housing undersupply, increasing interest rates does not do anything to diminish demand for rentals. In fact, it has the opposite effect. Because higher borrowing costs reduce the number of people that can get finance to build a new dwelling, the RBA’s strategy is actually having the opposite effect. It is keeping more people in the rental pool at a time when Australia’s population is growing, while at the same time, it is reducing the future supply of housing to help moderate rental growth.

Returning to the supply and demand charts earlier, the other lesson from Economics 101 is that when supply diminishes at a faster pace than demand, prices actually increase as the same number of people are competing for fewer goods. That being said, if we are looking specifically at Australia’s rental market, we are actually seeing an increase in demand and a decrease in supply.

The following chart shows that this is a textbook economic recipe for rapid price escalation:

Compounding this supply shortage is the fact that higher borrowing costs encourage landlords to pass on rental increases more aggressively. When interest rates are low, landlords are more likely to be lenient with tenants in rental negotiations, but as the landlords cost increase they seek to recoup their higher costs through rent When the market is tight, tenants will pay what it takes to stay in their home, that means that landlords will push the limits of the market rent.

As a result, rents are growing at their fastest pace in 30 years and are not likely to stop any time soon. This has clearly accelerated since the RBA started increasing interest rates in 2022.

Sadly, the big winners of the RBA’s strategy are baby boomers that are already asset rich and have no mortgages.

The baby boomers, who are mostly out of the workforce, have made more than $4.3 trillion in equity over the last 20 years alone as a result of the house price growth that has occurred. The majority of baby boomers own their homes outright, and a large portion of them also own investment properties with no debt. As rents are rising rapidly, it is increasing the cash payments being made to these baby boomers who are on a spending spree – unimpeded by higher interest rates – going on holidays and eating out.

The other winners are property investors that have an established portfolio, the majority of which have loan-to-value ratios of less than 50%. Investors that have been active for more than 2 years have benefited from price growth that has reduced their LVRs to an average of 50%, while most have also paid down the principal which reduces their future borrowing costs at the same time their rental income is increasing. This is creating a cash bonanza for property owners that have held their properties for many years.

Therefore, the RBA’s efforts to put up interest rates to minimize housing costs and take spare spending money out of the economy are hurting the least affluent and benefiting the most affluent.

Looking outside of housing, the RBA’s efforts are also unlikely to impact the cost of fruit and vegetables, or the cost of energy, which are all considered essential household items and the supply of each is heavily dependent on environmental factors. Higher borrowing costs will not substantially reduce demand.

WHAT ARE OUR TAKEAWAYS FROM ALL THIS?

The RBA playbook doesn’t work when there is a housing shortage that is increasing the biggest cost in the household budget. Rents will continue to rise rapidly due to less supply and more demand. When the RBA realizes their mistake and pauses interest rate increases, there will be a huge rush from pent-up demand as renters try to get out of the rental market. Many will be trapped in the rental market paying higher rents long into the future.

The mixture of pent-up demand and rising rents will lead to a quick rebound in house prices, and ultimately to much higher house prices over the coming years.

And the upshot of all this is that the benefits once again will go to existing homeowners and inequality will get worse.

This means – contrary to the cautious approach – now is a good time to buy, whether as an owner-occupier or as an investment property.

The benefits are certainty of future payments; they reduce the impact of interest rate fluctuations on recent purchasers and their tenants.

So, while the headlines swirling around right now may be creating hesitancy, those with a clear and robust plan to buy can benefit from the effects of interest rate rises on the market – just not in the way the RBA intended.

Watch our latest webinar to learn how to use the current market conditions and starting building wealth today.

Click here to register.